Origins of the Word ‘Filibuster’

When Senate Democrats acted last week to end filibusters as we know them (at least for certain appointments), cries and sighs were heard on both sides of the Congressional aisle.

Sighs came from the Dems, who now could put in a federal post any person living or dead, criminal or upright.

Cries of injustice rang from the GOPers. Had the Republicans pulled the trigger on the so-called “nuclear option” back in the mid-2000s when they controlled the Senate, however, roles would’ve been reversed with Dems crying affront to democracy and Repubs cheering, at least under their breaths.

Republican Gov. Rick Perry of Texas was livid earlier this year when State Senator Wendy Davis filibustered the legislature in Austin over an abortion bill. The good guv called it “nothing more than the hijacking of the democratic process.”

Which brings up the origins of the word filibuster, and for this I rely on the research and writings of Merrill Perlman in the Columbia Journalism Review:

Of “filibuster,” The Oxford English Dictionary says, “the ultimate source is certainly the Dutch vrijbuiter,” or “freebooter,” “a privateer … a piratical adventurer, a pirate; any person who goes about in search of plunder.” From the 18th century to the middle of the 19th, the OED says, the preferred term in English was the French “fibustier.” But about “1850-54,” the OED says, the form “filibuster,” from the Spanish filibustero, “began to be employed as the designation of certain adventurers who at that time were active in the W. Indies and Central America.”

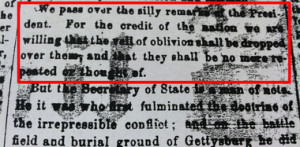

The word filibuster began taking on a legislative slant about mid-century (1850s or later) when “someone in the Congressional Globe wrote: ‘I saw my friend … filibustering, as I thought, against the United States.'” (Note the verb usage.)

In 1889, the noun version of filibuster appeared, referring to the person blocking the action, not to the act itself. Within a few years, the noun filibuster was being applied to “an act of obstruction in a legislative assembly,” the OED says.

In other words, as Perlman notes in his article, equating a filibuster with a hijacking is not without historical and linguistic justification, regardless of which side of the aisle you or your senator sits.